Sunday, April 27, 2008

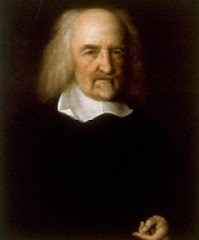

Hobbes on human nature

Would you characterize Hobbes's view of human nature as pessimistic, or merely realistic? Although he seems to adopt something like the later Bentham's "predominant egoism", he also acknowledges humans' tendency to form "transcendent interests", interests in the service of which they are willing to risk death , or embrace death. If the goal of political philosophy is to display, as Rawls insisted, a realistic utopia, can Hobbes's conception of human nature be a building block in anyb realistic utopia?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

5 comments:

That's a really cool post. I just thought you might want to know your blog got mentioned on PEA soup.

Interesting question! On the one hand, I think any realistic utopianism takes the appropriateness of a social system to human nature as a criterion of its perfection. At the same time, utopianism must allow for the possible equal maximization of every individual's wellbeing. So the answer depends on whether or not Hobbes' egoism is fundamentally at odds with the latter. And that, I suspect, depends on the degree to which his egoism is opposed to other-regarding interests: are egoistic and transcendent motives distinct and opposed, or are transcendent interests ultimately grounded in egoism?

I do find it interesting that most people's intuition tends toward the assumption that an egoistic theory of human nature is "pessimistic." I'm inclined to think most obstacles to utopian have their basis in group motives and behaviors that aren't clearly or directly egoistic. This may mean that it's "transcendent interests," not individual self-interest, that pose the problem for utopia.

I'm not sure what would justify "equal maximization of wellbeing" as the standard, but I do agree that uniformity-requiring transcendent interests cause horrible problems, both for bare social stability, and for any kind of principled social unity among diverse factions. Is liberalism made impossible?s

My maximization of well-being criterion was a rough stab at giving some content to the idea of a perfect society--if someone's well-being is not maximized, it may be a good or justifiable or the best possible society, but not a perfect one.

I wonder if you could say more about how you view the problems of transcendent interests? I had in mind factionalism--which may be based, not in a requirement of uniformity, but rather in a demand for distinction, where one group defines itself in contrast to another, thus defining its interests in an oppositional way that can't be harmonized on the social and political level.

I'm not sure about the liberalism question. Why do you think it might be impossible? Is this given Hobbes' egoism or the problem of transcendent interests?

CK,

I think of transcendent interests-- those interests people are willing to risk or sacrifice narrow self-interest in the pursuit of-- as causing trouble for social stability either when there is the sort of factional opposition among them which you suggest, or when some have a uniformity-requiring content, so that they demand that other people conform to their requirements. The latter sort will be illiberal, it seems, since they are willing to use state power to enforce conformity with their own requirements.

I think this sort of problem can be generated without any reliance at all on assumptions of egoism. Greg Kavka had a very interesting paper (published posthumously) arguing that even morally perfect people (perfectly conscientious agents holding faultless moral beliefs) would still need government because there could arise conflicts among them over the practical requirements of morality-- in which they could hold transcendent interests-- requiring authoritative adjudication. (I don't actually think Kavka's argument works, but I think it does succeed in showing that even non-egoistic interests can prove socially problematic if they are held in a sufficiently principled or transcendent manner.)

Post a Comment